Saifur Rahman Tapon

The International Crimes Tribunal (ICT) has sentenced deposed Prime Minister and Awami League president Sheikh Hasina to death in the first case related to the July–August killings. As expected, the verdict has sparked satisfaction among the families of the victims, the injured, and other participants in the movement. At the same time, questions have emerged about what impact this verdict will have on the Awami League.

This discussion is important because, since August 5 of last year, more than five hundred cases have been filed against Sheikh Hasina in regular courts and the ICT, most of them murder cases. Inevitably, more verdicts will follow in the future—verdicts that will go against Sheikh Hasina and the Awami League. Additionally, the ICT has initiated investigations directly against the Awami League, and as a result, the party may face a permanent ban. In short, in the near future, the party that governed the country with dominance for nearly 16 years may face even more legal challenges.

Belgium-based International Crisis Group (ICG) has stated in a report that the possibility of Sheikh Hasina returning to politics is now slim. However, as long as she refuses to relinquish control of the Awami League, the likelihood of the party rebuilding its political footing remains low (Samakal, 18 November 2025).

Negative predictions about the Awami League’s future are not new. Many political analysts said strongly—especially after the fall of the government during the mass uprising and after most party leaders, including the leader herself, went to jail or into hiding—that the Awami League’s return to politics is impossible. The late leftist theoretician and politician Badruddin Umar said the party had met the same fate as the Muslim League. Some even said that if the Awami League returned after such a massive uprising, it would disprove political science itself. Monday’s verdict will only reinforce such beliefs.

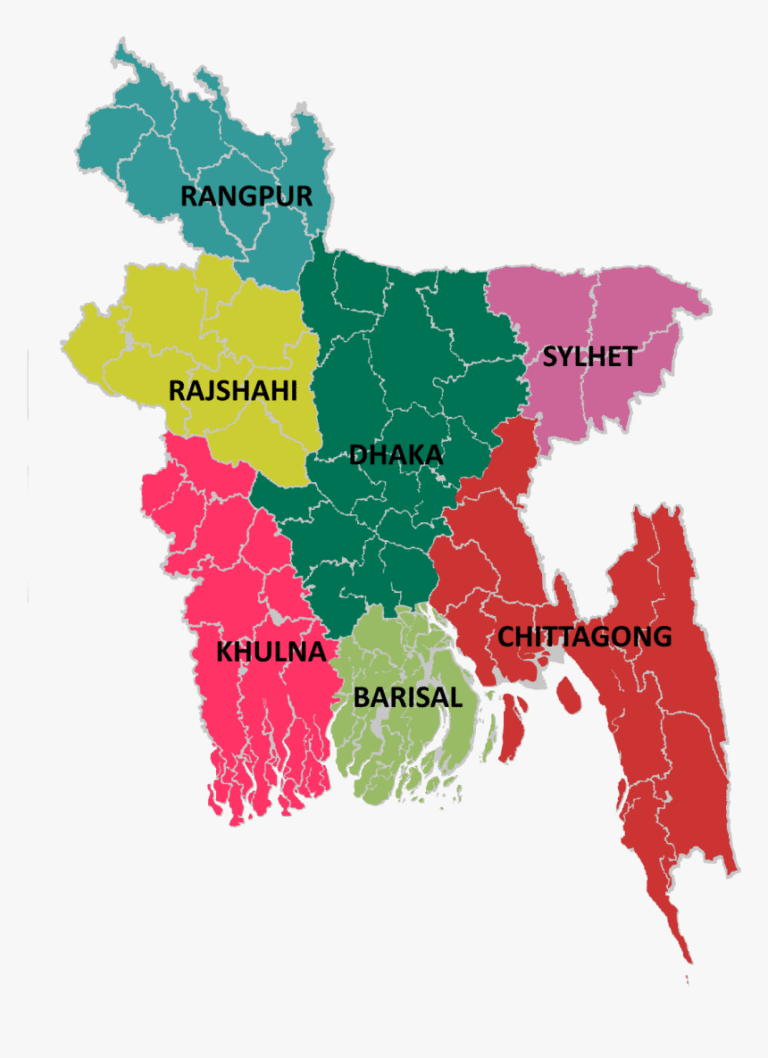

Another factor has strengthened such perspectives: the party’s limited impact surrounding the verdict in the crimes-against-humanity case. On November 13, the day the verdict announcement date was set, the Awami League called for a “lockdown” in Dhaka. Amid the party’s activities and the government’s heavy security measures, the program initially drew some attention. But on November 17, when the verdict was announced, the party declared a nationwide shutdown that had minimal effect on public life. While some flash processions were seen on Dhaka’s streets in recent weeks, none were visible on verdict day. Aside from scattered gatherings in Gopalganj, Bhanga in Faridpur, and parts of Shariatpur–Madaripur, the party’s presence was very limited across the country. This reinforced the perception that the myth of the Awami League being a “party of movements” may have collapsed. In reality, the party is now a “lame duck.”

This idea seems justified when reviewing the party’s governance over its last three consecutive terms. The Awami League came to power in 2009 with the support of nearly half of the nation’s voters. But within five years, it became unpopular for various reasons. The party gradually exiled democracy, and an oligarchic influence emerged within the government. The party itself became controlled by opportunistic factions with no ties to grassroots activists—the heart of the organization. Consequently, the party’s structure collapsed alongside the government. That collapse became evident on August 5. If the Awami League tries to rebuild itself on that abandoned structure, the expected results are unlikely.

Even so, there is little room to disagree with Professor Sabbir Ahmed of Dhaka University’s political science department, who said, “If there are loopholes in the verdicts, they will widen divisions among political parties. Especially Awami League versus anti–Awami League politics will become even more ruthless” (BBC Bangla, 18 November 2025). In other words, negative actions by anti–Awami League forces—particularly regarding democratic norms, good governance, and justice—may inadvertently revive the party’s relevance.

Political events always carry multidimensional impacts—direct and indirect. The events of August 5 are no exception. One cannot deny that one of the movement’s core pledges was not only to uproot authoritarianism but also to end decades of confrontational politics. The interim government supported by the movement repeatedly said it would build an inclusive political ecosystem involving left, right, and centrist parties. Unfortunately, the political balance gradually shifted from the right to the extreme right, where the Liberation War became the primary target. As a reaction, public sentiment surrounding the Liberation War surged again. Without a viable alternative, this sentiment has largely benefited the Awami League.

It must be remembered that the Liberation War not only gave birth to this state but also created a new national identity—an identity that no political ideology can deny. Moreover, unless a new party emerges that can embody the central spirit of the Liberation War, the Awami League—the party that led the war—will continue to have scope for revival according to political theory. The party’s grassroots, shaped through the Liberation War and subsequent democratic movements, are reawakening.

Undoubtedly, grassroots awakening does not guarantee the Awami League’s resurgence. However, it does signal the possibility of a return. The failures that the opposition celebrates are rooted primarily in the actions of the disconnected leadership, not in the grassroots. These grassroots activists enabled the party’s comeback after similar crises in the past. The current political scene still revolves around Awami League versus anti–Awami League forces due to the solid and active grassroots. The flash processions seen today are driven by this base. It is also possible that from this continued momentum, a new grassroots leadership may emerge—one capable of re-establishing authority in politics.